What do you think?

Rate this book

123 pages, Kindle Edition

First published November 3, 2022

Time collapses as the value rises, bossman turning away complaints, a fifty pence scratching through the code quickly becomes a ten pence dragged across the numbers that disclose.

A day becomes every other and weekly silences quiet her enthusiasm for home. They are too busy, she thinks, but itŌĆÖs her, sheŌĆÖs the one who is here.

The distance between death and life proclaims absences unbearable. Distant glimpses of waning villages assuage the emotions of scarcity.

She stops calling and spends more time with her brood of thoughts; she finds extra shifts to take her mind off what sheŌĆÖs lost.

This isnŌĆÖt it, though ŌĆ� he thinks of who should be the one to care for her.

Norm-switching form and a Union Jack sways outside the home sheŌĆÖll die in.

Does she know who he is, does she not care or has the atrophy made her unaware, who is there, a few drops left of memory.

He canŌĆÖt take it, her, what is this, Ghanaian or not she planted her seed to bloom over here, wafts of western idiosyncrasies pungent to her frail identity.

On Sundays her hand slips into his, a light renewal of platonic perfection, until her son becomes someone elseŌĆÖs reflection, the face of so many she loved but could never tell, though she always shows warmth to whoever approaches her church.

To watch a mother become a woman, deteriorate to become a girl, an infant who canŌĆÖt be held, waiting, unaware, to submerge with a familyŌĆÖs final and stifled breath.

This is where she should be. Briefly, to see him smile sheŌĆÖll remember it was him, and sheŌĆÖll stretch her arms, an embrace with no charm, ingratiated with this terra, hell, an immigrant mother who will die here alone and can only rise with the body of work her son has done well.

I made the creative choice not to translate any Twi in my book and also decided against a glossary. So many reasons for this but mainly it's because many West African kids didn't have any of that either. Our parents regularly refused to teach us. Had to figure it out. Welcome

'XXXV

Her hand rubs her spine

A son steps foot on her back

Relief through labour

You okay, Mum?

My back.

You want me to walk on it?

Mmm

Okay.'

My mum had one of them laughs that the harder it goes, the more it starts to sound like that cartoon character. That duck one who never wore trousers. Actually, that's jokes because mum was the opposite. Ghanaian mums don't see breasts like the rest of the world, it's mad. Bruv, obviously I'm not talking about my mum's breasts. Low it.

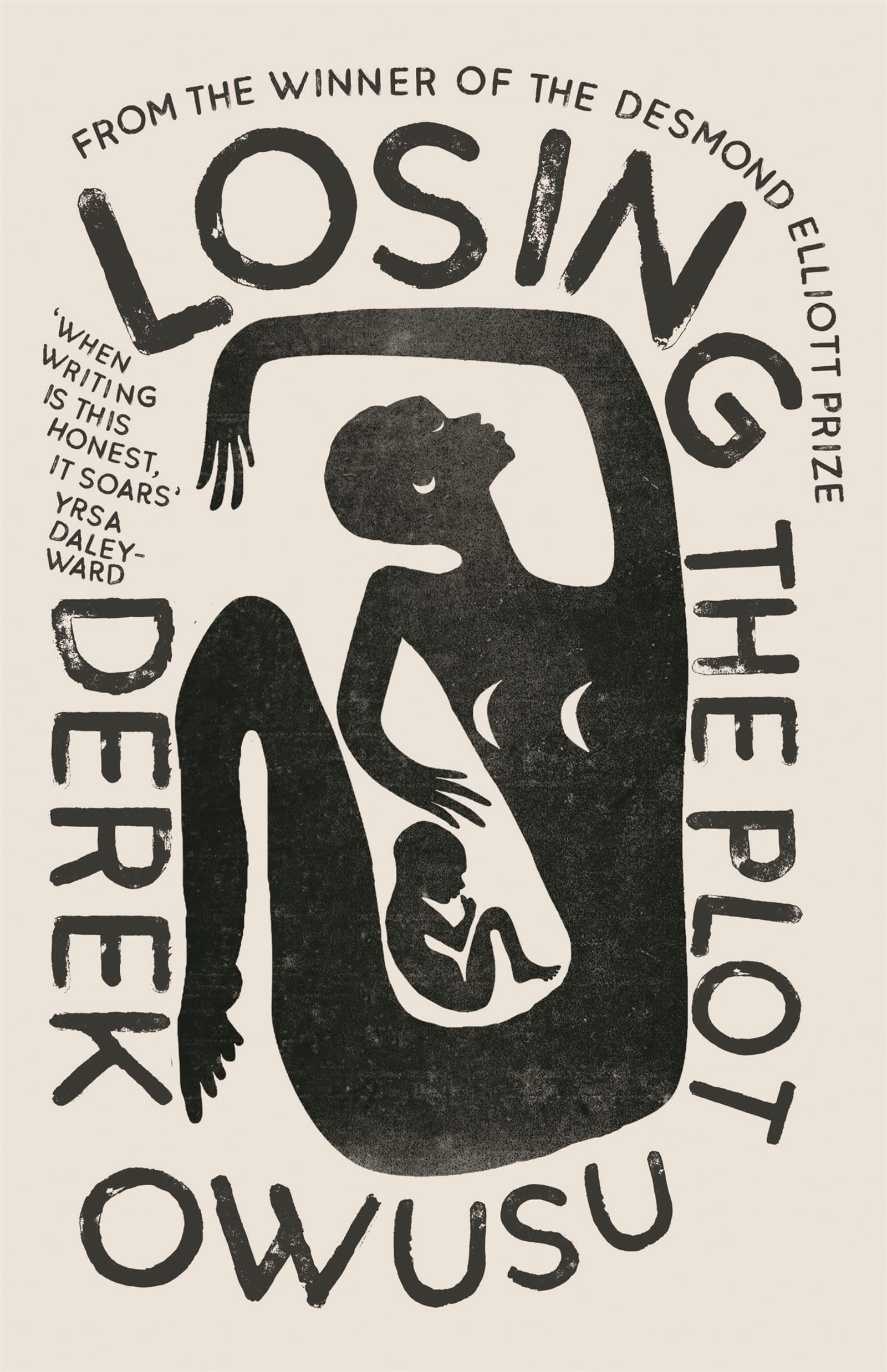

HeŌĆÖs always wanted to ask what she hoped to achieve, ŌĆświthout meŌĆ�, without displacement, without history, a sentence without words to follow, a life without a plot. SheŌĆÖd say, sheŌĆÖd make life, what that means, heŌĆÖs never known, looking back, what she sees, he needs to let go, let her be.

She was sent away, told Auntie would watch her from now, because the house was too small and she was the eldest, sheŌĆÖd had more life with family, her arguments not allowed to conclude even though when she lands, new documents will read her younger than every sibling.

The binding piece shrivels, though she

returns to it every day; sheŌĆÖll mother every

piece of him, even if parts must be taken away. Will she stroll through another childhood with dusty and deserting feet.

Will she cry when hands reach, will she

let her son suffer her defeat.

He prefers son to any other calling, loves the drop of tone through those three letters, sounding stretched but comfortable in their balance, a name heŌĆÖs proud of, a lustrous designation so small but brilliant, a reaction of love touching his entire body when his mother summons him with such a small word capable of palpitating all the air around him. He forgets annoyance, every anger an act when love struggles to escape.

Yes, Mum.