What do you think?

Rate this book

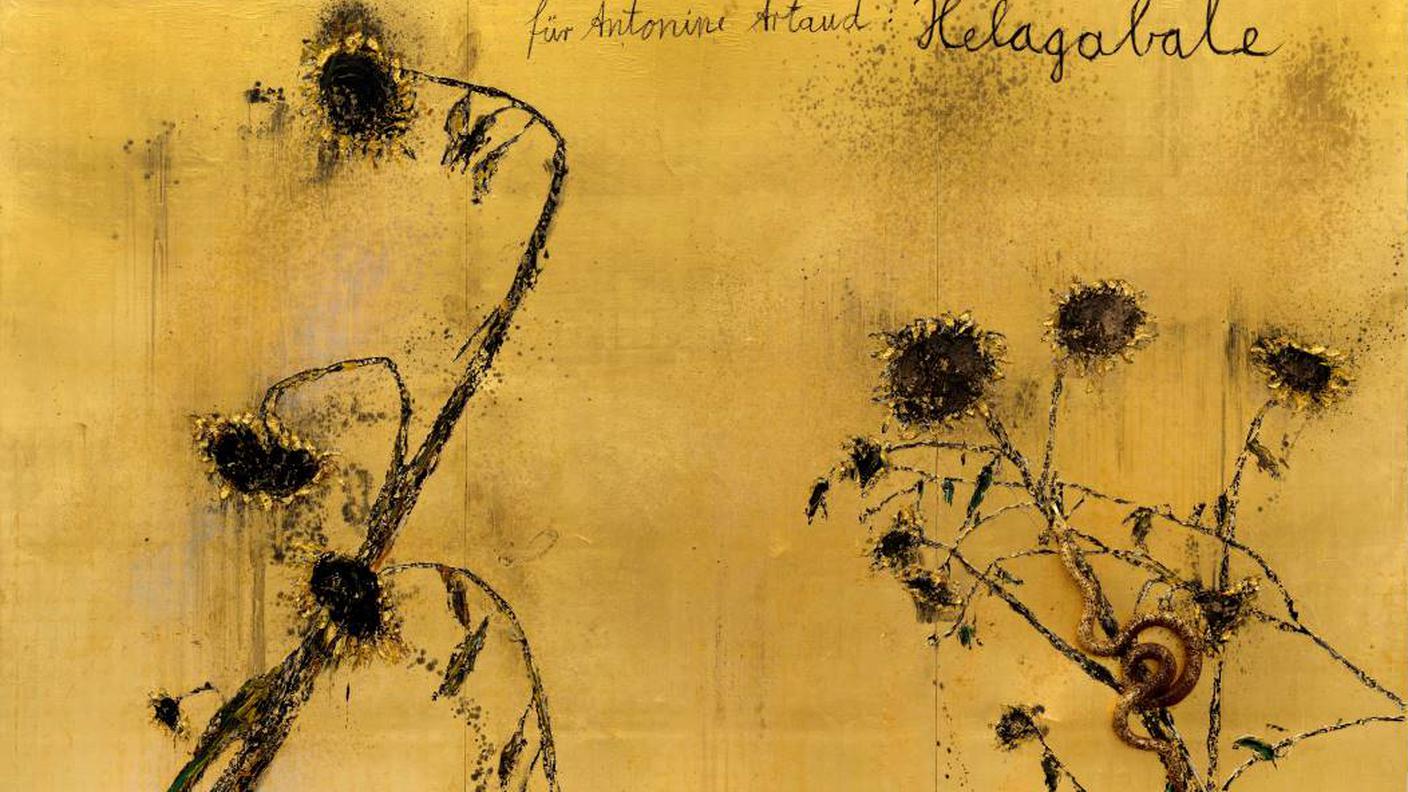

Heliogabalus is Artaud's greatest and most revolutionary masterpiece: an incendiary work that reveals both the divine cruelty of the Roman Emperor and that of Artaud himself. -- Stephen Barber

154 pages, Paperback

First published April 1, 1934

A thing named is a dead thing, and itŌĆÖs dead because it is set apart.

Principles are only of value to the mind, and to the thinking mind; but outside the mind that thinks, a principle is reduced to nothing.

Voice Claudia also describes the history of a potential, and probable, active-trait male in her territory. He declared himself a living god-emperor, and through marriage to Bene Gesserat Livia produced several generations of active-trait males. One appears to have been the first known Abomination, a man who heard ŌĆ£voicesŌĆ� and claimed to be both male and female, but whose actions were so perverse that Voice Claudia refuses to describe them. (ŌĆ£Bene Gesserit History,ŌĆ� , p. 121)*

All the same, Heliogabalus the pederast king who wanted to be a woman, was a priest of the Masculine. He achieved in himself the identity of opposites, but did not achieve it without harm, and his devout pederasty had no origin other than an obstinate and abstract conflict between Masculine and Feminine. (p. 72)